Protected: The loss of the Lady Cairns, 1904

It was a cold morning in March 1904. The sun was only rising. The fog was so heavy even the light struggled to shine through. One could smell a storm brewing in the breeze. The waves punched the hull of the barque Mona with violence. She was heading southeast as the mist got hazier and hazier. The deep cries of her fog-horn reverberated around and strayed into the fest. It was almost impossible to guess the Kish Light, barely 12 miles away. Unexpectedly, the crew realized they weren’t alone. They heard the blasts of another horn coming from their starboard bow. They looked and saw nothing. Only the lookout man noticed an over-canvassed ship (with no lookout of its own) on its port bow. Only half a mile away. The pilot tried to slow the Mona by bracing her sails aback. Alas, it was too late. Both vessels collided and the mysterious ship sunk in the Irish sea in minutes. The cries of the 18 souls of the crew faded into the wind.

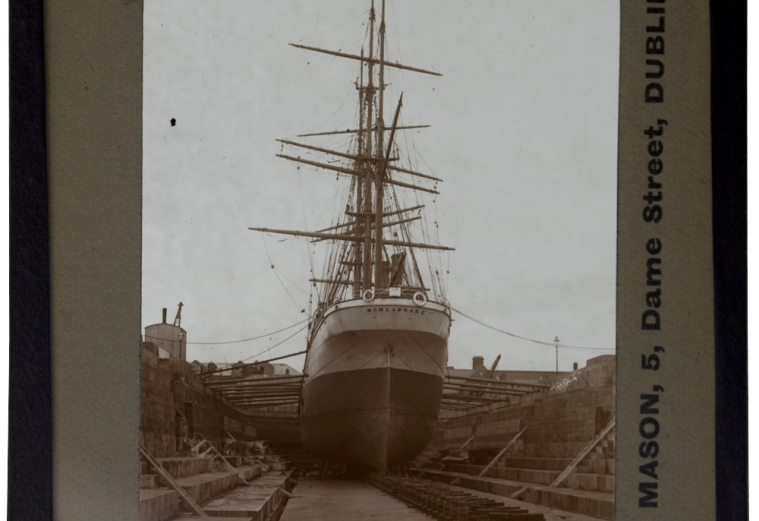

The sunk ship was the Lady Cairns, an iron sailing ship built by Harland & Wolff in 1869. She was an old acquaintance of Dublin docks. Richard Martin (a prominent figure in the history of the docklands) bought her when he first went into the shipowning business. Not only he was a member of the port authority for over three decades, but also part of the Martin family, kings of the timber trade. The Martins sold the Lady Cairns to L.Tullock (Swansea) a few years after Richard passed away.

The event greatly stirred public opinion. Its importance was such that James Joyce mentions it in his masterpiece Ulysses. While Bloom is in a bookshop nearby, an elderly lady left the Four Courts, having heard the case.

But why? Maritime accidents were not uncommon. Dublin was used to these tragedies. The bay was notorious for shipwrecks.

What really rubbed salt on the wound was that no effort was made by the Mona to assist. When they collided, Mona’s sailors relentlessly started to get their lifeboats ready. They had two. Only three men onboard volunteered to take one lifeboat and attempt a rescue operation in the blindness of the fog. The master ordered to wait until both lifeboats were ready. He was afraid their ship was also damaged and water coming in. However, once the boats were battened down, the master said the fog was too thick, the sea too choppy and they had already drifted so far from the scene. It would take more than half an hour to reach them.

The Court didn’t share the master’s views. Perhaps the Mona was not at fault for the collision. Both vessels failed to act with enough celerity when they sighted each other. The lack of survivors from the Lady Cairns prevented the courts from answering some questions. It was impossible to determine if they had a lookout and if their fog-horn was duly sounded.

However, the shipmaster and its pilot, John Gerald Schwarting and Peter Sharp, were accountable for denying assistance, abandoning the Lady Cairns crew to a cruel fate. There was enough evidence that at least part of the crew was about the wreck for enough time to form a raft by lashing together the for-and-aft bridges. That meant part of the crew survived a considerable time in the sea and that the sea itself was not as rough as Mona’s master had stated.

The Court concluded that the sea wasn’t unsafe. Hadn’t the shipmaster stopped them, the three volunteers could have saved some lives. A compass and the Mona making sound signals would have sufficed to find the way back in the thickness of the fog.

As to why the Lady Cairns was sailing under such a heavy press of canvas, why no lookout man was on the bridge, or why they weren’t sounding the fog-horn as they should is still a mystery.

The Mona bore up to Dublin after the collision and was repaired at Graving Dock no. 1

Help us with the Archive

You can help us to preserve Dublin Port’s rich archival heritage by

donating items or seek advice from us on items in your safekeeping.

Get in touch by completing the contact form below.

We’d love to hear from you!